January

The SPLC and the no good very bad white Christian nationalist but also just unpopular anti-LGBTQ+ pseudoscience network

This week, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) dropped a major investigation into “anti-LGBTQ+ pseudoscience”. Dubbed Project Captain, the report declares that the “network we identify supports and is supported by white Christian nationalist ideology that seeks to privilege straight, white, cisgender Christians in public policy and replace science and American law with Christian theology”.

The authors cast a strange and internally contradictory set of aspersions over the Enlightenment and “science” (their quotation marks, not mine), while deploying all the strategies they accuse their political opponents of practising. Then again, making sense of the opposition is not what this report is about.

Rather, it is the product of political necessity — the need to discredit the growing pushback to youth gender transition and gender self-ID policies that put males in girls’ sports and women’s prisons. One way to dismiss political opponents is by attaching as many of the following labels as possible: conservative, Christian nationalist, cisheteronormative, white supremacist, male supremacist, creationist purveyors of misinformation and pseudoscience. (In case that’s not enough to convince you, these views are also “unpopular.” We’ll come back to that.)

This is a ham-fisted attempt to lump all opponents together, regardless of their distinct values, approaches, or political orientations. The report then moves on to accuse the “anti-LGBTQ+ pseudoscience network” of “manufacturing doubt” by, for instance, using “critical reasoning and attention to detail” when evaluating counterarguments (guilty as charged?) and pointing out that developmental psychology and growing numbers of detransitioners suggest that trans identification may, in some cases, be transient and thus an unwise target of life-altering hormonal and surgical interventions.

The authors make the bold move of defining pseudoscience (“knowledge or conclusions we assume were produced by following the scientific method or best practices within a specific field of study — like psychology, psychiatry and various fields of medicine — but are not actually scientific”) while peddling it themselves, passing off unverifiable concepts like gender identity as established and unquestionable “scientific” facts.

Very human problems in the field of gender medicine

I wanted to respond to two major themes in the responses to my piece on the questionable beliefs and practices of gender clinicians, which can be summed up as “These people are evil” and “These people are idiots.”

I am not going to deny there are bad actors—and more than a few complete and utter nincompoops—in the field of gender medicine. But most of these people got into the field of trans healthcare in order to help people. That they wound up causing harm instead is a product of indoctrination into harm-as-help. It's not possible to understand where this field is today without understanding that.

I’ve gotten some criticism for being too soft on gender clinicians. I don’t think this is fair, exactly, but I understand where it’s coming from. I think it’s more important to understand how that happened than to label it as ‘evil,’ wash one’s hands, and be done with it. What’s happened in the field of gender medicine is a fascinating case study in human psychology: how do decent people end up doing terrible things?

Are there a lot of people in this field who should have hung on to their critical-thinking skills? Yes. But the process of enculturation in trans healthcare gets people to surrender their critical thinking in service of the cause. That's what being a good gender clinician requires.

The piece I wrote is full of examples of how this happens. You raise concerns about a patient and suddenly you're a gatekeeper, which is bad. You’re withholding life-saving medicine just because you feel a little uncomfortable about something in some patient’s case file, like an autism diagnosis or a history of self-harm.

Or you try to abide by standard medical practices and then you get berated by a patient who says she would have killed herself if some other surgeon hadn’t been willing to break the rules and cut her breasts off despite her morbid obesity and the risks that poses during sedation and recovery. Do you want to be responsible for your patients committing suicide all because of some numbers on a scale?

The amount of emotional blackmail and hostage-taking in this field is hard to convey to outsiders. It’s everywhere. Of course this kind of pressure bends clinicians who—at first contact—knew better.

The thing is, gender clinicians talk openly about this! They say, oh, when I first started seeing these patients, I was really uncomfortable with the kinds of procedures they wanted or I thought [insert eminently reasonable critique of altering the body to placate the mind here].

Then they overcame those hangups and became true trans allies who didn't put their cisheteronormative (or whatever) biases ahead of what they came—over time and under immense ideological pressure—to believe was best for their patients.

What kids are looking for—and finding—online

My presentation to a parent group about online indoctrination into trans identification and gender distress:

Something that comes up a lot is the fear of faking being trans for attention or social clout, or as a result of peer or online influence. Members of online trans communities tend to draw a sharp dichotomy between “faking it” and “not faking it” that they then use to reassure themselves that they are NOT faking their trans identity because their feelings of distress are real. So, when young people confess that they’re worried they may be faking their trans identity, they will be reassured that fakers know they’re faking it, they’re bad people, they’re making a choice, and so if you’re worried you might be faking it, that’s a sure sign that you’re not.

But the idea that young people are “faking” a trans identity, I think, misses the mark. What’s happening is much more subtle. You can have sincere feelings, real distress, a sincerely held interpretation of what’s going on—and your sincerity or the severity of what you’re experiencing has nothing to do with whether that interpretation is in fact rooted in reality.

Trans identification and transition often appear to be motivated by rejection of maleness or femaleness. This often seems like a much stronger motivator than any positive embrace of masculinity, femininity, or whatever it means to be nonbinary today—or by discomfort with sex-role stereotypes and expectations (e.g., expectations around expressing femininity), being treated like or seen as a woman (for example, one poster wrote about hating “the way people look at me like I’m some delicate little lady who shouldn’t be taken seriously”),” and being uncomfortable with female body parts and functions. Girls in particular will often say they once belived that other girls felt this way but then they learned about trans identities and realized their feelings made them not normal girls but trans boys.

Pathological body projects in the pages of Teen Vogue

What this interview and the photo shoot that accompanies it—which portrays a fresh-faced young woman draping and exposing her body for the consumption of unseen others—show is how dangerously misguided the demands for trans and nonbinary representation are. Trans is an idea. It is not a neutral or inconsequential idea. It is an idea that can lead young women to reject themselves and cut off their breasts. This idea is now being packaged and sold to girls and young women in glossy magazines the same ways a hundreds of other forms of female insecurity and discontent are packaged and sold in these very same pages.

Sadists and masochists

In which I check in on my old field, public health. Things are not going great!

How do you know if you’re the one who needs to be re-educated? Well, maybe you feel ‘uncomfortable’ being accused by name of perpetuating white supremacy for bringing up Roe v. Wade!

Wanted to add, for those feeling discomfort during hard-but-necessary conversation: discomfort signals a need for growth.

Discomfort, of course, is not nearly so reliable a signifier. You can feel discomfort for all kinds of reasons. Sometimes, you might feel discomfort because you’re in the wrong, but sometimes you might feel discomfort because you’re being treated like you took a shit in the swimming pool for being insufficiently self-flagellating.

Meanwhile, around the perimeter, a bunch of people with desk jobs eagerly lob kindling on the fire:

Let’s be clear, when folks are engaged by in public health activism in this way [just to be clear: “this way” means offering up civil criticism of an idea on a private listserv…], you are harming the very people you intend to benefit from your activism (people experiencing structural violence).

Questioning causes harm. (Don’t ask how this works—or else you’ll be causing harm, too!)

February

Where did all the weird nerd women go?

Eliza: What made you decide to dig deeper into the issue of gender?

Nicole: The short answer is: I wanted to understand why women like me–weirdo nerds with Autism diagnoses who love to write and draw–were so likely to decide we weren’t women.

The long answer is: the toll of being asked to accept so many remarkable things added up over time. I had questions that weren’t getting answered. I read every pro-trans article anyone linked on social media hoping that this would be the article that finally made sense, only to be disappointed. For a long time, I thought I was the problem, because when I first encountered the trans stuff, I was coming to terms with the fact that some of my other beliefs about how the world worked weren’t true, so I figured, well, this doesn’t make sense, but just because I don’t understand something doesn’t make it not true. I don’t always understand things when I first encounter them, especially when those things involve other people’s experiences. I was keenly aware that my inability to understand other people’s point of view was lacking, and that was something I was actively trying to work on at the time. So I said OK, fine, I don’t get it, but that’s me. I’ll keep trying to understand.

But, as time went on, it became harder and harder to believe. It was upsetting to realize that I’d spent years arguing that women could be weird nerds… only for all the other weird nerd women to say “Oh, no, we’re not women, actually.” It was easier to go with it when it was just the occasional slash-obsessed person coming out as trans and wanting to look like a J-rocker. But it came to the point where, whenever I joined a new fandom discord or a discussion forum or something, I’d know that everyone would be female and that none of them would put she/her in the pronoun field.

Actually, at one point I caved. I joined a discussion group and I felt so awkward being the only person to use she/her that I put he/him. I justified this to myself by thinking, but we all know that everyone in this fandom is a woman, so it doesn’t matter. Anyway, it turns out we do not all know, which I found out when someone asked for advice and I gave it and everyone said, “Wow, how could you be so insensitive, you can do that because you’re a man, but we’re AFAB [assigned female at birth], so we can’t.” These trans-identified women then took it upon themselves to spend the next several months educating me about the female experience. (And I never told them the truth, because I’m an asshole and wanted to see if they would ever catch on. They didn’t).

When I decided to dig deeper, I didn’t trust anyone invested in gender to give me accurate facts because my experience with both liberal social justice culture and the conservative culture I grew up in was that facts are less important than demonstrating group loyalty. Most of the weird liberal nerds I know would be greatly offended if I said this to their faces because they believe that rejecting their parents’ value system demonstrates that they’re independent thinkers who aren’t swayed by group loyalty or peer pressure. But they are. They simply chose to cast their allegiance with a different group. They enforce this new group’s norms very stringently, in fact. There are all sorts of fun little hashtag events for creators on social media, and so many of them have rules that say things like, “If you’re transphobic you can’t participate.” “If you don’t believe in self-diagnosis you can’t participate.” “If you don’t have all the exact correct opinions you can’t participate.”

I want to say that I don’t think this underlying impulse is inherently negative. Having a group is a necessity for our survival. But this kind of blind loyalty can have negative consequences, depending on the group norms. And it’s vexing when you want to have a conversation about a topic that has become a “Group Loyalty Test.” Because you can’t. It’s the worst.

Stories from under the overbroad “trans umbrella”

You can’t say the trans community doesn’t have range. Really, there’s far too much variation nestling under the ‘trans umbrella,’ to the point that it’s downright misleading to bring all these people together and suggest that people with such diverse experiences and motivations have anything meaningful in common.

That’s what these Reddit stories are about: the many types of people who come to think of themselves as trans—from Eurovision fans to lonely teens to girls in flight from objectification and the men running toward it—and why and how they came to think of themselves that way.

March

Fan fiction “tenderized my brain”:

Members of online FTM/transmasc communities tend to talk about fan fiction and anime the way they talk about sexual trauma or autism. Of course, someone can be trans and also have a traumatic past. Of course, you can be trans and autistic. Everything is incidental. Sure, I read a lot of fan fiction in the years before I came out as trans. You could even say I was obsessed. But one thing didn’t lead to another. Their self-understandings are pure and untouched in the way that nothing is ever pure and untouched. But to be human is to be adulterated, to be the ever-changing composite of influences chosen and unchosen.

Maybe consuming fan fiction was a “dysphoria coping mechanism” or maybe it was an irritant, the strange incubator of impossible desires and intolerable discontents.

Along the way, community members drop hints about the underlying reasons fan fiction was so appealing. These accounts are heavy with heterosexual despair: “i cried myself to sleep over never being able to experience the kind of love i liked to read about so much,” one poster wrote. “This was the only way I was comfortable exploring my sexuality,” another observed.

Detransitioners finish the sentences that trans-identified girls and women let trail off. Fan fiction offers sex and romance without baggage, without sexual inequality, and without risk. Or, sometimes, simply: it turned me on. It didn’t mean anything.

“When you have been taught that heterosexuality is too dangerous but still have the natural urges the vast majority of females have, well, there you are.”

“I never saw myself in female characters. They were always flat or stupid to me. (Internalized misogyny? Also bad writers) I only saw myself in male characters”

“I probably romanticized homosexual content because they couldn’t have any unwanted or accidental pregnancies… I still identify as childfree and I don’t want to become pregnant.”

“I read lots of gay male fanfic because I had sexual urges but found male/female sex triggering because of my sexual trauma. I fetishised gay male relationships and could only ever see myself enjoying sex if I was a man. I felt safer as a man.”

“I think I love yaoi not just because I find male characters aesthetic, but because I only like to see characters that are not my own biological sex doing it, I feel great discomfort from sexualizing myself, and by extension other women.”

“I began to identify with these representations of boys written by other young females, and the themes within male/male fanfiction were so much more titillating than anything in mainstream, professionally produced media, or even heterosexual fanfiction for that matter. The pairing being same sex seemed to give writers and readers the freedom to explore these characters and their relationships without being constricted by the norms that come with heterosexual dynamics. It became this liminal space where I could explore what interested me about boys and fantasies about relationships, connecting it to whatever my media obsession was at the time, without the pressure of interacting with real boys, as real boys made me painfully bashful.”

“To me, it felt more neutral and lightweight, not as burdened with… um… gendered tropes let’s say? … I believed (or was at least strongly influenced by) sexist tropes, and the gay constellation set me free from that. Like more of an eye-to-eye relationship where you’re both just persons rather than fulfilling a role, and everything remains cozy and romantic no matter which way you play.”

These are not new problems and desires, but old ones that have vexed and inspired generations of female artists and writers, animating works of fiction like Ursula K. Le Guin’s lovers in kemmer, who go to bed genderless, uncertain which partner will rise expecting a child. These are the sources of the harnessed rage that runs under Adrienne Rich’s poems and musings, and that guided the pen in her hand when she wrote that “the body has been made so problematic for women that it has often seemed easier to shrug it off and travel as a disembodied spirit.”

Some girls really, really, really want out

Taking female adolescence as the context in which both disorders must be understood, Alexander Korte and Gisela Gille explore the serious developmental challenges every girl must confront on the way to adulthood. Girls are often sexualized and objectified at early ages, before they have the emotional maturity to make sense of these experiences and often before they themselves have begun to explore their own sexuality. As Korte and Gille put it, “Sexuality is discovered in a girl before it unfolds within her… girls experience an external sexualization of their bodies that still bears little connection to their own feelings.” As a result, girls may suffer embarrassment and confusion and may blame themselves for attracting unwanted attention. These feelings may be triggered or exacerbated by exposure to violent and degrading pornography, sometimes shared by male schoolmates in an effort to induce “shock or shame.” Girls who have experienced sexual abuse are at particular risk. Trans identification and other disorders rooted in the desire to control or reject the body may arise as “trauma-compensatory reactions” or extreme forms of adaptive dissociation.

Girls must also confront the ubiquitous objectification of the female body, depictions of sexuality that “shows little or no respect for girls’ age- and gender-specific feelings,” the media’s promotion and celebration of trans narratives, the relentless promotion of “self-optimization and the possibilities of body modification” more broadly (for example, in the desire for cosmetic surgeries to alter the appearance of the genitals to conform to new aesthetic norms); and the “very conspicuous, sometimes voyeuristic fascination in our society for self-harming behaviors, especially among young women who submit to trends.”

So it’s really no wonder that adolescent girls tend to struggle with a “split” between their changing bodies and their evolving sense of self. Reconciling body and self is an arduous process and many girls and young women take detours along the way. These detours may include efforts to “stop time” by refusing to eat in the case of anorexics or by seeking puberty suppression in the case of trans-identified girls. Anorexia and gender dysphoria arise when an adolescent girl fails to maintain a sense of coherence between body and self and must employ desperate measures in order to cope.

Andrea Long Chu’s greatest hits

The blaze-orange cover of this week’s New York magazine screams: “FREEDOM OF SEX: The moral case for letting trans kids change their bodies.” The author is Pulitzer Prize-winning author Andrea Long Chu, who returns to spill onto the page all the revolutionary inanities other comrades-in-arms might prefer to leave unsaid.

This is nothing new for Chu, who has long played the role of the unstable relative who airs the family’s dirty laundry at every public event, ignoring angry looks and admonitory “shhhhhhs!” from loved ones.

In a 2018 New York Times op-ed, Chu griped that “my new vagina won’t make me happy and it shouldn’t have to”. The writer went on to detail a precipitous mental decline since coming out as trans (“I was not suicidal before hormones. Now I often am.”), while railing against any attempts to gatekeep life-altering interventions.

Chu’s 2019 book Females revealed the source of this unhappy new identity: “Yes, sissy porn did make me trans.”

This week in New York magazine, Chu sets about dismantling what little respectability the trans movement has been able to defend against its own radical fringe. Forget doctors and parents! Screw caution! Don’t protect the kids! Down with expertise and common sense! Up against mounting evidence of medical harm and growing caution from the general public, Chu lays the case for child medical transition shockingly bare: “We must be prepared to defend the idea that, in principle, everyone should have access to sex-changing medical care, regardless of age, gender identity, social environment, or psychiatric history.”

Chu appears to have received the same set of briefs as other trans activists: 1) Everything is “gender-affirming care” now, even your mother’s hair dye and your father’s Viagra. 2) “[I]f children are too young to consent to puberty blockers, then they are definitely too young to consent to puberty.” 3) Changing your mind is no big deal. Life is full of regret (so why bother listening to all those detransitioners?). Chu suggests, “Let anyone change their sex. Let anyone change their gender. Let anyone change their sex again.” 4) Redefine everything. Redefine keeping trans-identified boys out of girls’ sports as “patriarchal” and white supremacist (somehow). Redefine sex as changeable. Redefine reality as optional. 5) When all else fails, accuse your critics of defending their own fragile gender identities, as Chu does by suggesting that women such as J.K. Rowling “too might have transitioned given the chance, so intensely did they hate being teenage girls”.

But Chu’s too-clever arguments spill over into transparent lunacy.

“Gender, like genitalia, is represented by diversity”

How does a professional organisation respond when a scandal breaks? Some issue smooth denials, leaving not so much as a seam for critics to pick at. Some finger bad apples. Others dare to admit faults and strive for transparency. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) took a rather different tack, issuing a bizarre statement this week in response to the publication of files exposing malpractice at the organisation.

WPATH President Dr Marci Bowers begins by marking the territory (“We are the professionals who best know…”) and appealing to authority (“widely endorsed by major medical organizations around the world”), before moving on to distort the conflict (the WPATH files are not, in fact, a bid to “de-legitimize” anyone’s identity). The stray comment about the shape of the world attempts to paint critics as anti-science, the equivalent of flat-earthers.

Bowers then asserts that “gender, like genitalia, is represented by diversity”, which sounds like the sort of meaningless twaddle Google Gemini cooks up. Bowers wraps up by twisting the stakes (patients “deserv[e] healthcare”) and minimising the scope of the organisation’s work (“small percentage of the population… [that] will never be a threat to the global gender binary”), a plea in effect: leave us alone!

The statement is nonsensical because the brief was impossible. WPATH needed to speak simultaneously to two entirely different audiences — the world outside and the organisation’s own membership — who needed to hear entirely different things.

For decades, the field of gender medicine has insulated itself from scrutiny and criticism. The public and policymakers were never supposed to get a glimpse into the inner workings of the field. They were supposed to defer to the “experts” and not look too closely at what they were being asked to support.

The WPATH files look much too closely, shining a spotlight on risks and uncertainties and harms so specific that they will be difficult to forget: patients with tumours, patients whose ages and developmental delays and serious psychiatric conditions mean they could never meaningfully consent to the interventions they underwent, patients who regret being sterilised because they now want children. These files provide fuel for policymakers seeking to regulate youth gender transition and patients trying to sue. The fallout is just beginning.

WPATH’s members, on the other hand, need to see this brutal exposé as a devious plot against a noble cause. WPATH has been preparing its membership for just such a faith challenge for years, instilling an embattled mentality. For years, the organisation’s conferences and events have promoted the narrative that gender clinicians are a misunderstood and persecuted vanguard within medicine who will be vindicated in the future but must suffer heinous accusations in the here and now.

April

My conversation with Democrats for an Informed Approach to Gender

What inspired you to launch Democrats for an Informed Approach to Gender?

For me, Democrats for an Informed Approach to Gender grew out of my experiences as a parent who was blindsided by this issue when my child came out as “trans”. That sent me off on the typical liberal parent journey where you’ve already been somewhat brainwashed to affirm and rush your child to a gender clinic, thinking that the gender clinic will see this path doesn’t make sense for your child. So I did all that. I consented to puberty blockers. I got deluged in misinformation from the gender clinic claiming that all of this is exceptionally well-founded, based in the best scientific practices. And then I did my own research and figured out that this was just dangerous, incoherent nonsense, and that I had to find some way to get my kid out of it—which I haven’t been able to do yet.

The thing is, at first you think that surely there are tons of intelligent, well-connected people out there who are going to expose this scandal for what it is, that this is something we somehow got caught up in but somebody is working to fix it. You know, the calvary is coming. I had that in my mind. And then it became apparent that, no, the cavalry was not coming. If anybody is going to save our kids from this, it’s going to be us parents.

After a year of disappointment, where I was trying to help my kid who was really decompensating and seeing what was happening in my own family, I realized that nothing was going to change unless we could open the eyes of Democrats to what they were supporting and how far they had veered from liberal values. It’s hard to accept that institutions you’ve put your faith in your whole life have lost their way like this. That’s when the ground beneath your feet really falls away. I’ve been a liberal Democrat my entire life, from a family of liberal Democrats, and all of a sudden, my party turned into a monster. They’re the bad guys.

Democrats have to be led out of this by the hand, gently. This won’t end if that doesn’t happen. They’re hurting people. The Democrats are participating in the destruction of families and the grievous harm of young people and children. Some irreparably or to the point where they can’t live with what’s happened to them anymore.

Online trans communities as zero-gravity chambers

The Reddit community r/questioning describes itself as “a helpful community for those questioning their sexuality and/or gender.” In practice, online communities like this serve as one of the first stops along a process of indoctrination, a place where people newly confused about gender find their disorientation and dissociation reinforced.

Take this 15-year-old, who started questioning her gender two years ago, who identifies herself as “possibly FtM” [female-to-male]:

My thoughts are more often “I want to be a guy” rather than “I am a guy”

But sometimes, I sort of stand where I stand and from my own perspective am standing there as a guy. Until someone passes by and goes “good afternoon young lady”.

Basically, sometimes I feel like I exist in the world as a guy – but living as a guy feels unreal. I’m born female, I guess that’s what I’ll live as. There’s not point even changing it, the first 15+ years will always have been lived by a female version of me.

It feels really weird and alienating and kind of painful to call myself a girl (even typing this just…). And being called by my name or she/her feels like being stabbed and it’s so triggering, but that only started recently after like 2 years of questioning. Although any other pronouns or names that I use online sometimes feel alienating as heck. He/him is weird and feels a bit funny (idk how I feel about it), they/them is basically as triggering as she/her.

My sister often tries to insult me by telling me that I look like a guy. I really hate it when she does it. Not really because she calls me a guy – it’s just, I need to defend myself and say “nah, I’m a girl” or something like that and the sentence just doesn’t come out right. And sometimes my mum will ‘help me’ defend myself by saying “No, she really looks like a girl”. or something and I just get triggered.

I don’t even know if I have dysphoria. People say it’s like hating your body, but I don’t feel that way. I don’t mind my body as a whole or something like I feel neutral about it but also a bit disconnected. I don’t really see my body as something connected to myself or something – it’s just there when I look in the mirror. But the way shirts and pants fit me because of my chest and thighs does make me want to rip off my head. I can still look at those parts standalone though, but I hate them for destroying how I look in clothing and making me hate swimming.

Lower dysphoria-wise, in a lot of situations I want male parts, but I don’t hate whatever I have right now. I still don’t want to describe it, refer to it, talk about it, interact with it or have people interact with it in the future or whatever (I might also be asexual though).

Unfortunately I can’t really experiment with gender expression until I’m a legal adult. I don’t know about men’s clothes, but women’s clothes don’t really work for me.

I have sort of talked about questioning with a friend of mine, who is trans himself. Sort of explaining these kind of thoughts (although more focused on body things and I never specified disliking my name or she/her or whatever). And he seems to agree that I am a cis girl. He does say that what I feel might be dysphoria though. But in a cis woman way or something?

Edit: probably forgot to mention a lot of things, I will likely add whatever I want to later, but one thought I had was that I can say “I want to be a guy but I don’t want to be trans”, because it’s true. But I can’t say “I am a guy but I’m not trans” and that hurts a bit. It’s not possible.

And another addition: I feel like if I were (am?) trans, it’s already too late. I might have fucked up 15 years and even if I came out right now and got on a waiting list or something, I would be 17 or 18 by the time anything would happen. And at that point my body would already be hopelessly poisoned by estrogen puberty.I started questioning myself at age 13, but still haven’t figured out if I’m trans or not – I’m 15 now. If I were (am?) trans, wouldn’t I have been sure in those 2 full years? Surely I would have. But still just living my everyday life it just doesn’t sit right and it takes so much energy.

TLDR; there’s plenty of reasons that I ‘am not trans’, but I keep coming back to questioning everything.

She describes everything feeling weird—he/him, they/them, she/her. She writes about feeling triggered by her own name, but then notes that she only started feeling that way recently—“after like 2 years of questioning.”

She feels disconnected from her body and cannot avoid objectifying herself. She doesn’t talk about her body as something she inhabits—the “radiation” of her “subjectivity,” as Beauvoir put it—but as something she sees in the mirror, something that “destroys” how she looks in clothes.

Like many teenagers, she is uncomfortable with her body and its potentialities. She doesn’t want to “describe it, refer to it, talk about it, interact with it or have people interact with it in the future or whatever.” She thinks she might be asexual, but she might also just not be ready for the sexuality she sees everywhere on display.

She’s being bullied by her own sister and struggling to defend herself. She has trans friends, who only confuse her further. (What does it mean to feel dysphoria, “[b]ut in a cis woman way or something?”)

She wants to be a guy, maybe, but not trans. She recognizes the impossibility of this desire. If she carries on in online trans communities, she may forget these limits later. She may pursue something she once knew she could never become, something she knew would never be enough.

Like so many young people further down the road to transition than she is, she has that clock already ticking in her head. Maybe 15 is already too late. She imagines herself coming out and spending the next two or three years on a waiting list: “at that point my body would already be hopelessly poisoned by estrogen puberty.” The pressure is on.

After two years of questioning, she feels like she should know the answer. But she cannot let it go. Because she cannot reject the idea, because she cannot pin anything down—least of all whatever it might mean to be a ‘guy’ or a ‘girl’—she cannot move on.

The strange world of tulpamancy

I stumbled upon tulpamancy after years of studying some of the weirder corners of the Internet: places where bizarre self-diagnoses, fragile identities, and dangerous desires bring perfect strangers into community with one another. I’ve come to see these spaces as carefully sealed chambers for the management of belief and doubt, and many of the dynamics I’ve noticed there reappear in the world of tulpamancy.

There’s the same hesitation to draw any lines, to exclude any experiences from consideration and validation. “Has a host been pregnant with a tulpa?” one user asks. No one quite wants to rule the possibility out. “I would believe it would be possible, but not physically—the whole experience would be imagined, as tulpas are nonphysical entities,” someone offers. That is to say, it would be imagined and real at the same time. “Biologically, that is extremely improbable bordering on impossible.”

There’s the thrill of disembodiment that haunts every online space, the perfect embrace between idea and medium. Online, tulpamancer and tulpa can be equally real, equally present. Another way to say this is that, online, tulpamancer and tulpa can be equally unreal.

Users frequently open their posts and comments with attributions, like the stage directions for a play. [Enter Charmander, stage left.] ‘Tulpas’ and ‘hosts’ take turns speaking. They defend one another, heap praise, and prop each other up. They seek the kinds of recognition they will never find offline, where no one understands.

Only the community understands, a community many refer to as their only source of companionship—apart from, of course, their tulpas. The basis for this connection is their shared retreat from the real world. It is astonishing how far it is possible to retreat. A life that has flattened out offline becomes ever-more flattened here. School, work, family—whatever there is that is not this—falls away.

As I read along, I find myself wondering: what kind of stories are these? Sometimes I see things that the storytellers wish I wouldn’t. Inconvenient details crowd around the edges of each upbeat narrative: fractured bonds, extreme social isolation, difficult pasts, a certain faith with the world that has been broken. Occasionally, stragglers wash up on the shores of this strange island: confused parents or discarded partners who wonder what they did wrong, why imagination won out over reality.

“[D]oes a tulpa make a good friend?” one woman asks. “I have intense social anxiety and I have a hard time making friends. Would creating a tulpa help with this? My husband has told me many times that I need to find someone to talk to besides him for everything.”

There’s something indecent about seeing these private refuges laid so bare, like seeping wounds left uncovered. Some part of me wants to say: keep it to yourself, for your own good. Even if—especially if—what happens in these fantasy worlds sustains you, you should never let anyone see these things. These Wonderlands are at once precious and obscene.

Cracked eggs and "baby trans": Trans infantilization

Spend any time whatsoever in trans spaces and one of the first things you’ll notice is the rampant infantilization.

There are grown adults snuggling with cuddly toys and blaming every kind of negative emotion and social transgression on going through “second puberty” (sorry: still not a thing!). They try to recreate the childhoods and rites of passage they never experienced: giggly sleepovers, bubble-gum pink, sparkly lipgloss and painted nails, truth or dare, learning how to shave and tie ties. They cling to childish hobbies and interests, like Pokémon or Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles or My Little Ponies, or overidentify with the underage aesthetics of anime. Middle-aged men dress up like schoolgirls, tugging frilly knee socks up over their bony joints and tying bows in their hair.

Trans-identified adults fantasize about do-overs: if only they’d been allowed to transition before puberty struck. Everything would have been different. The fantasy of starting over and blocking puberty helps keep the promise of transition intact when it would otherwise fall apart. Transition didn’t fail because it was a mistake. Transition failed because this pharmaceutical intervention was withheld from me as a child. That, and children make a more appealing face for a movement that struggles with optics. Thus, activists enlist children in an adult cause, trading children’s open futures for talking points and political cover. Activists rally around children and conceal what’s unsavory about the movement behind their innocence.

Then there’s the endless talk about “eggs” (people who are supposedly in denial about their trans identities): the moment you realize you’re trans is described as “hatching” or “cracking your egg.” New members are often referred to—or refer to themselves—as “baby trans” who need to be shown the ways of the strange new world they find themselves in. There’s the expectation from many activists that their feelings ought to be handled with kid gloves and—indeed—far too many grown-ups end up placating activists as though they were fussy toddlers.

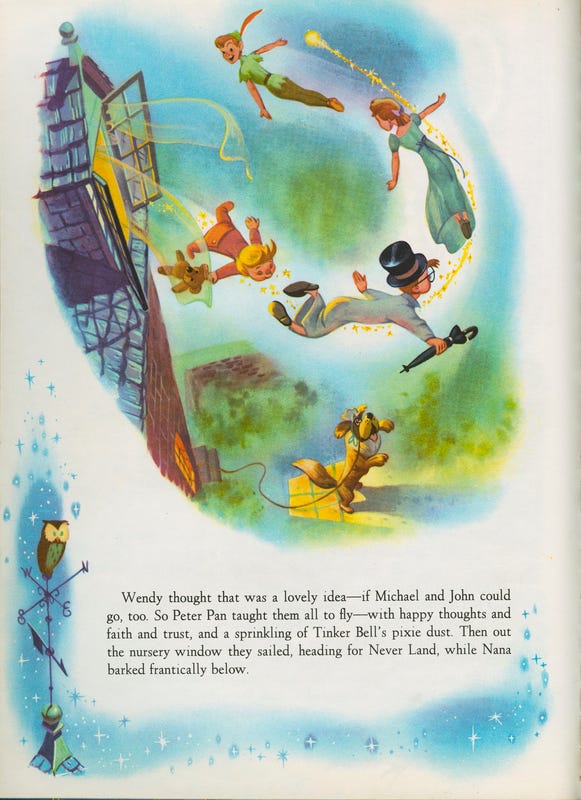

There are many ways to interpret the disconcerting childishness of trans communities. “Peter Pan Syndrome.” Plain-old immaturity. Many trans-identified individuals seem afraid to grow up, as though they worry about their ability to meet the world of adult responsibilities. For these people, ‘trans’ is a cul-de-sac or a cocoon, a substitute for meaningful growth and change. And then there are some men who appear to fetishize childhood the way they fetishize womanhood, feeding twisted fantasies that they ought to have starved.

But there’s something else going on here, too.

May

"We just don’t sabotage our lives for no good reason."

Because doubt is ever-present in online trans communities, the need for reassurance is bottomless. Bids for reassurance take many forms: Tell me I'm not the only trans person who didn’t ‘know’ when they were six. Tell me it’s got nothing to do with trauma. Tell me it’s just my internalized transphobia. Tell me you were anxious before you started testosterone, too. Tell me you feel the same way I do.

People seem to find consolation—however temporarily—in sentiments like: I don’t know what I am but I know I’m not a girl. I don’t know what to call myself but I know I don’t want these breasts. I don’t know where this is going but I know I can’t keep living like this.

And then there’s what I’ve come to think of as the backstop: appeals to the adversity transition inevitably entails: Why would I tear my life to shreds if my trans identity weren’t real? Who would *choose* to live life on hard mode*?

Or, as a recent commenter on r/FTMOver30 put it, in response to a young woman seeking a balm for her anxieties about transition: “We just don’t sabotage our lives for no good reason.”

No, you see, this is very important. You must understand. We are compelled to sabotage our lives. We had no say in the matter.

It’s always easier to say “I can’t” than “I won’t,” to take refuge in the impossibility of doing otherwise. One hears this kind of language all the time in trans spaces. But the equation—transition = sabotage—is breathtaking, betraying what it was meant to conceal.

When being a “boy” and being a “girl” are seen as equally performative and self-falsifying

Because my research focuses in part on experiences of feeling like an imposter, the subject of “passing” as a member of the opposite sex comes up a lot. There’s the constant self-monitoring, the agony of not passing, the mingled thrill and terror of succeeding.

But the other day, I ran into an interesting use of the term on the r/actual_detrans subreddit by a young woman who identified first as transmasc, then nonbinary, and had taken testosterone. She wrote:

I am worried I am not pretty enough to be feminine: I’ve always been chubby and I think a lot of my dysphoria and desire to be masc has been just because I didn’t think I could pass as a pretty feminine person because of being chubby.

Here we find the language of “passing” applied not just to passing as the opposite sex but passing as an “acceptable” member of your own sex. The implied equivalence between these two sorts of passing is interesting and gets at the way femininity feels like a performance or affectation for many girls.

For many girls, “passing” as an acceptable member of your own sex class still means being thin enough, pretty enough, and feminine enough. The band of acceptable femininity is perilously narrow, and the equation of femininity with being female is pushing girls toward transition.

I still remember the girls who could never do anything right, whose effort and lack of effort were equally persecuted by our peers. Attempts to beautify yourself, if you were not considered beautiful, were laughable pretensions (“Why bother?”). There was no opting out, either (“Wow, so-and-so really gave up”). There was no way to insist on other terms. You either “passed” or you failed by some mysterious, ever-shifting standard.

This was pre-social media, pre-filters, pre-fillers. And there was no escape via trans identification. So the pressure has gone up and a valve has opened to vent that pressure. Girls who struggle with the impossible and often contradictory expectations girls and women face—and the peer pressure and bullying that comes down on girls who cannot or will not conform to these expectations—can opt out now.

June

Putting yourself on a medical leash in the name of bodily autonomy

New research in the International Urogynecology Journal raises serious concerns about testosterone use among trans-identified female patients. Researchers found that 94% of the patients they studied had developed pelvic floor dysfunction since starting testosterone. What’s more, 87% suffered from issues with bladder control; 53% reported sexual dysfunction, such as pain during intercourse; and 74% reported experiencing issues with bowel movements, such as constipation or faecal incontinence.

In an interview with the Telegraph, physiotherapist Elaine Miller warned that young adult females taking testosterone appear to be on “exactly the same trajectory” as women undergoing menopause — except that they’re encountering these issues 20 or 30 years ahead of schedule. Miller spoke about the toll complications like this can take on a person’s life: “Wetting yourself is something that just is not socially acceptable, and it stops people from exercising, it stops them from having intimate relationships, it stops them from travelling, it has work impacts.”

There’s a serious disconnect between emerging evidence of transition’s risks and harms, and the ways young people view these interventions. In the online spaces that I study, young people talk about their bodies using casual, often dismissive language, as though they were embarking on a do-it-yourself home-remodelling project. They talk about how they prefer their bodies to run on “T” (testosterone), not “E” (oestrogen). They deride puberty as “oestrogen poisoning” or “testosterone poisoning”. They are also startlingly alienated from their bodies’ natural functions, always seeking fresh euphemisms to hide uncomfortable realities, such as the young woman who wrote that she could only cope with the “dysphoria” her period caused by “seeing it in a[n] impersonal and logically [sic], usually thinking ‘The cycle is occurring to this vessel.’”

Young people and gender clinicians alike increasingly speak of detransition as no big deal — just another stop along an edifying journey of self-discovery. Jack Turban and Johanna Olson-Kennedy, two of the leading gender clinicians in the US, refer to “dynamic desires for gender-affirming medical interventions”. Others prefer the term “retransition”, which suggests a kind of equivalence between the initial decision to intervene on a patient’s healthy body and any subsequent interventions on an altered body. Olson-Kennedy has waved away concerns about potential surgical regret among her young female patients: “If you want breasts at a later point in your life, you can go and get them.”

But transition — and detransition — is nothing like customising an avatar or tearing out a kitchen. What hormonal and surgical interventions can offer to patients struggling with gender dysphoria is severely limited. When these interventions “succeed”, they imperfectly imitate physical features and functions that medical technology cannot, in fact, replicate. When these interventions go wrong, the complications can be life-altering, even fatal. Meanwhile, every intervention takes an unpredictable toll on the body. Over the coming decades, as this mass medical experiment plays out, I worry that we will see growing numbers of young people suffering from the kinds of diseases and disabilities that typically emerge only in old age.

To make matters worse, researchers also expressed concern that patients may avoid seeking help for transition complications, citing fear of encountering discrimination in healthcare settings, as well as discomfort and distress dealing with body parts and functions. Patients may also fear losing access to interventions they have come to believe are not just identity-affirming but life-saving. Discussions in online forums frequently turn to complications patients are reluctant to bring to their doctors’ attention, lest they lose access to hormones.

For all the trans community’s talk about bodily autonomy, there’s little focus on the ways medical complications can strip away the freedom to live one’s life as one pleases. Young people flocking to gender clinics today may not realise what life on a medical leash means. Too many will find out in the course of time.

“I still hate that I just want to be everyone else.”

Like so many girls who come out as trans, she opens with a heartbreaking expression of what it’s like to struggle with feeling like a human subject, not a sexual or decorative object: “When I came out as not a girl, I went from feeling like a thing to feeling like a person.”

But what stands out most to me is her hunger after meaning. She has a weak sense of self because she is “chasing what makes me feel good” through clothes and haircuts and other attempts to change how the world perceives her. To be fair to her, she comes right out and says this—“I feel like I just mirror everything around me and wear masks to be perceived how I want to be perceived”—though she doesn’t quite connect the mirroring and masking to her (frustrated) attempts to find meaning and legibility through the medium of gender. “I still hate that I just want to be everyone else.”

These girls don’t just want to become someone else, they want to become somebody at all. They’re grasping for templates that don’t wound and offend them. They’re trying on masks, looking for the one that will create the right impression and secure the right kind of recognition. In other words, they’re engaged in the developmental process of identity formation—but only in the most superficial sense of the term, working from the outside in, cutting themselves off not just from the reality of their sex but from their actual interests and inclinations, which are reduced to props that either undermine or support the gender they want to project.

After “help me manage my doubts and cognitive dissonance,” “tell me how to enact my authentic self” is the second-most popular genre on trans Reddit.

My testimony for Quebec's Comité de sages sur l'identité de genre

Until recently, researchers, clinicians, and parents understood something a lot like gender dysphoria to be a normal stage of adolescent development for teenage girls. Simply put, it is hard to grow up female. It can be hard to accept the changes to one’s body—like menstruation and breast development—and the way society responds to those changes. There have always been girls and young women who sought a way out of the developmental challenges puberty posed. They took off-ramps like anorexia or cutting. Today, trans identity is a super highway promising an escape from the discomfort of female adolescence. My research suggests that adolescent and young adult females are responding to common developmental pressures and seeking to fulfill basic developmental tasks through trans identification. This is not the same thing as being in any sense ‘born in the wrong body.’

Many of the young females I see in online trans communities are seeking an explanation for the distress they feel over their changing bodies. They often struggle with questions of identity. They may not know how to fit in with their peers. They are looking for a place to belong, a sense of direction in life, a purpose or cause to devote themselves to, and recognition for their uniqueness and for the changes they undergo as they move from childhood toward adulthood. They are also often looking for a scapegoat for difficulties in life. The belief that one is transgender offers a clear scapegoat: the female body itself, which can be disciplined into compliance with the new identity regime, much the way the anorexic disciplines her body through starvation. A transgender identity can be especially appealing when healthier developmental pathways are blocked, for whatever reason: because the whole world locked down during a pandemic, because a young person has too few friends and opportunities in real life, or a too-compliant personality, or because mental health difficulties and neurocognitive differences interfere with her ability to build a compelling life offline.

As you can see, there are a mix of healthy and unhealthy impulses and needs that drive girls and young women to embrace gender. Once they do, they embark on a trajectory that has become familiar to me after reading thousands of such accounts online. This trajectory begins with exposure, being prompted to identify oneself with a gender. Young people are constantly prompted to make these kinds of self-identifications online and offline, and they quickly learn that what you choose says a lot about who you are.

Being prompted to identify yourself with a gender is often the first time a young person gets the idea that your gender is a choice—and that selecting a gender is not a straightforward statement about whether you’re male or female but rather a loaded question about who you are, deep down, and what ‘side’ you’re on in the conflict over social justice. And if you’re questioning your gender, then you’re—by definition—not “cisgender”: you are some flavor of trans. To put it simply, having a personality means having a gender. And having a gender means being trans.

If you have the misfortune to question your gender online, you will be encouraged to experiment in all kinds of ways, large and small, some of which can be binding on future choices, and all of which attach a great deal of attention and importance to gender, which can create distress where none existed before or make ordinary adolescent discomfort worse. Sometimes, the distress comes first and the trans identity comes second. Sometimes, the idea of being trans comes first and the distress comes second.

Now what?

Reflections on the end of my grad-school career:

When I arrived at McGill, I was prepared to be lonely. I expected that my research interests—asking inconvenient questions about untouchable identities—would isolate me. But I had no interest in playing ketman and I’d had some hands-on experience with ostracization. I thought I could handle it. At least this time around, I could choose the reasons for my own unpopularity.

It turned out I didn’t need to be so pessimistic. In mid-September—when the days were still warm but darkening fast—I met with a group of fellow graduate students at the foot of Mont-Royal. We went around and introduced ourselves and what we were studying. When it was my turn, I said simply, “I’m studying gender identity. I think it’s way more complicated than being ‘born in the wrong body.’” I half-expected the gathering to chill. Instead, my classmates—who had tensed at my first sentence—seemed to breathe a sigh of relief after I’d spoken the second. By expressing my doubts, I had created a space for uncertainty. Everybody had questions and concerns of their own, especially my classmates who came from clinical backgrounds, who had worked with gender-distressed patients up close and couldn’t quite bring themselves to see their patients as those patients longed to be seen.

Most of this was new to me because you wrote it before I was aware of your Substack. You have a remarkable ability (earned through practice, I'm sure) to avoid the use of third-person pronouns when writing about people like Andrea Long Chu and Marci Bowers without making your writing feel awkward or stilted. Impressive!

Wow - and that's part one! Thank you, Eliza, for your dedication to this topic, to this fight, and for your thoughtful, honest perspective. Keep up the good work and stay well.