Escape routes

Everywhere I turned, I sensed that I was being coerced into a conversation with the world that I did not want to have, sentences put in my mouth like a horse's bit.

When I think about being child, I think about how there was no seam that I could detect that indicated that my body and my self had been stitched together. I ran, climbed trees, flew between the uneven bars. Everything I did, I did with my whole body, even if I was only sitting in a chair swinging my legs.

But when puberty hit, the seams showed themselves and raveled. I went from living in my body to watching my body. It started when I realized I was being watched, that my body had become public property, and that my intentions and the meanings my body gave off had parted company. I couldn’t accept that I couldn’t control what people saw when they looked at me. As a child I got teased for being a tomboy, but only when climbing trees or scuffing my knees. I could stop doing those things anytime I wanted. But now it didn’t matter what I did. Everywhere I turned, I sensed that I was being coerced into a conversation with the world that I did not want to have, sentences put in my mouth like a horse's bit. I didn’t want to be seen, and I wanted to distance myself from the images I observed and then internalized of women whose bodies seemed to me like animated meat—for consumption only, not somewhere a whole person could live.

To defend my sense of myself as full human being rather than a maimed, incomplete one, I had to reject the women offered up to me by the culture I grew up in: the magazine-ad beauties; the tabloid headliners, always losing or gaining dangerous amounts of weight, always hiding something (plastic surgeries, lovers, ages); the evening-news victims of spurned men; the women whose misdirected energies rankled politics, that business of men. In literature class, I read dreadful, celebrated poems bound together in crisp, expensive books, in which women were wives and whores—whores at least providing more interesting subject matter—whose appetites, cunning, deceit, insipidity, and flesh brought down civilizations or ruined great—or at least promising, or at least young and not unpromising—men, or were brought down themselves, strangled fireside in neat verse, their human deaths losing shape and turning into allegories for the death of something larger, something that mattered.

I didn't feel the injustice of identification with these women. Who relates to a mask, a performance, a shell? Who identifies with a metaphor for a decadent, fallen society? I assured myself: I was an exception, praised repeatedly by teachers for my level head, for "not being like other girls," encouraged always to identify with the interests and perspectives of men, my true society. I dreaded puberty. My body was threatening to become what I'd been taught to despise. I started having nightmares where my body hardened into a statue even as I tried desperately to keep moving. I felt as though my body were a lie being put to me. My body—quite independently of me—was preparing for the ultimate betrayal, pregnancy, a fear not tamed by real information but grown wild on shame and silence.

Since I was growing up in the early 2000s, the form of escape that was available to me was to stop eating. I picked up the basics in health class, during a solemn awareness week. The film we watched was full of hints. I was nothing if not a fast learner, and I made an excellent anorexic: discreet and brutally efficient. I quickly disappeared. Over my teenage years, there were occasional interventions and referrals to specialists but I talked my way out of everything the way some young women now talk their way into diagnoses and treatment regimens. Long after I had starved away my breasts and my hips, they were all I could see in the mirror, a walking prison of flesh that threatened me. But that didn't mean that my self-perception was healthy or accurate. In reality, I was starving myself to death.

The sad thing is—it worked. Starving myself really was the escape from objectification that I needed it to be. I spent four years pretending that I was only my brain, my quick tongue, my sharp pen. I wanted desperately to be taken seriously despite my age, despite my sex. And I cut myself off from other girls, so their experiences couldn’t speak to me. I couldn’t see I wasn’t alone. My peers seemed to me to soften into their fates, while I whittled furiously.

I saw nothing fundamentally wrong with starving myself. It seemed not like an act of self-destruction but self-preservation. Besides, being hungry all the time gave me an electrifying energy and a sense of superiority. I had conquered my body. I had wriggled out of time. I don’t know that I would’ve stopped—but then I realized that my invisibility wasn’t as complete as I’d hoped. In fact, I was carefully observed by two little girls I nannied for. I noticed the elder sister, nine or so, pinch her flesh, comparing her soft body to my skeletal one. I realized with horror that I hadn’t solved anything. That I was setting an example they might follow. What I would never have seen as harmful to me I knew at once I didn’t want for them. I told her I was very sick and that she should never be like me. I forced myself to eat.

I was 17. Slowly, I moved back into my body. I learned how to see women differently. I read women. For years I’d shunned novels (unserious, especially ones by and about women). When I crawled back into their embrace, I was stunned to find them populated with women I recognized in myself, whose disappointments, frustrations, & secret rages I shared but never voiced. I began to see myself in Russian aristocrats, orphans, hijabis reading forbidden books. Some piece of me was distributed across the girls of The Group—in Libby's self-loathing submission to the editor parceling out her career one review at a time, in Kay's judgmental streak that skated on self-doubt.

I began to think of who I might be if 17, 25, or 33 years of social conditioning, hundreds of years of social organization, could be undone. I felt that I was not the human-person I should be—and not just because of my personal shortcomings and outright failures, which continued to pile up. I hated myself when I mistook sexual opportunism for sincere interest in my ideas. The pressure to be ‘sex-positive’ was intense, a jerry-rigged bridge over ignorance of the body, superstition, fear (real, reasonable), and an inequality I was not prepared to accept—boundaries pushed or declared ‘cute’ or ‘repressed,’ my body an instrument of someone else's pleasure, treated—at times—with all the care one visits on a sex toy, which can always be recharged or replaced. I felt that the real Eliza and the Eliza who lived in the world were not the same person, although the escapism of this troubled me. It reminded me of the line of thinking that led me to starve myself.

And I’ve been thinking about that line of Carolyn Gage’s: “I'm a freak. There's a lot of pain in being a freak, but there's a lot of respect. People have to deal with you on your own terms. They can't project their fantasies onto you.” I get that. I was a freak, too.

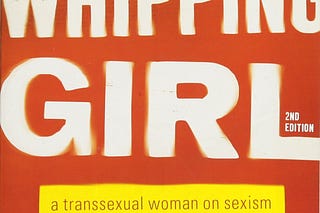

I’m still trying to figure it out, is what I’m saying. But I don’t want a way out that’s only for me. This is why I care so much about what I see gender identity doing to the generation of young women growing up after me. I get why that metaphor of being born in the wrong body speaks so powerfully. I've lived it. But enacting what is ultimately a metaphor for a deeper distress is not medicine. It's not progress.

I don’t think there’s a young woman who grows up free from the pressures of gender—no young men either, for that matter. But I don’t think more gender is the answer to the problem of gender, any more than starving myself was. I don’t think medicalization is the answer. I think we’ve got to try to live the answers—by living as freely and honestly as we can, and creating more space for the generation that’s coming up behind us, enough space for whole human beings to live in.

Thank you Eliza!