What kind of woman wants A Room of One's Own?

I got into a strange argument last night—all because of a once-beloved bookstore whose casual sniping at JK Rowling got on my nerves.

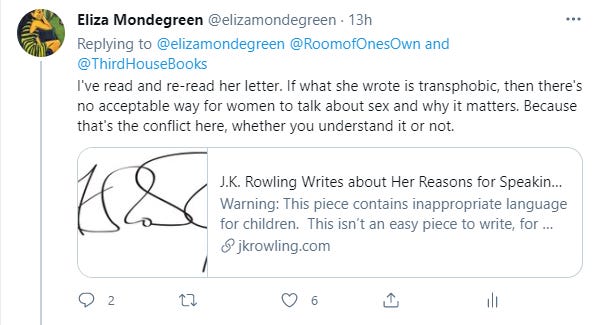

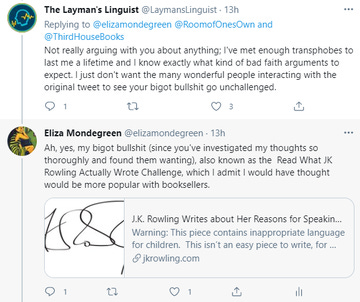

The bookstore responded first with misdirection, doubling down, offering – if I were possibly in “good faith” – to set me right. I only mention the next person to respond because what followed was so typical of this issue, underlining the exact point I was trying to make.

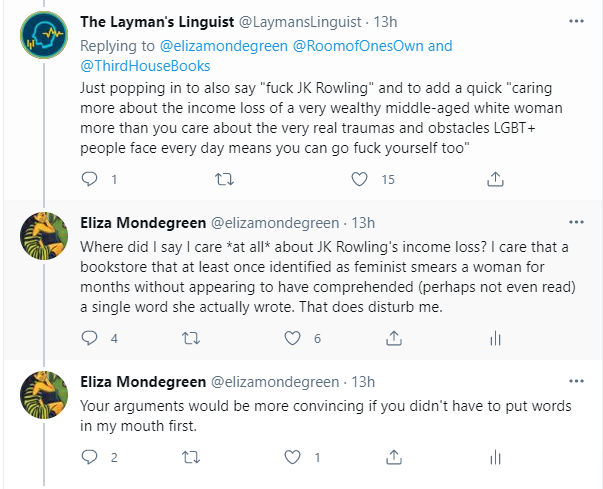

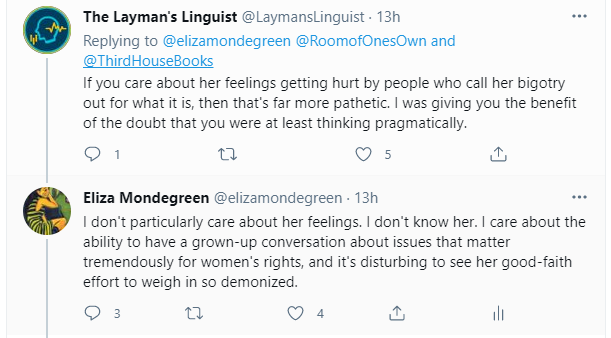

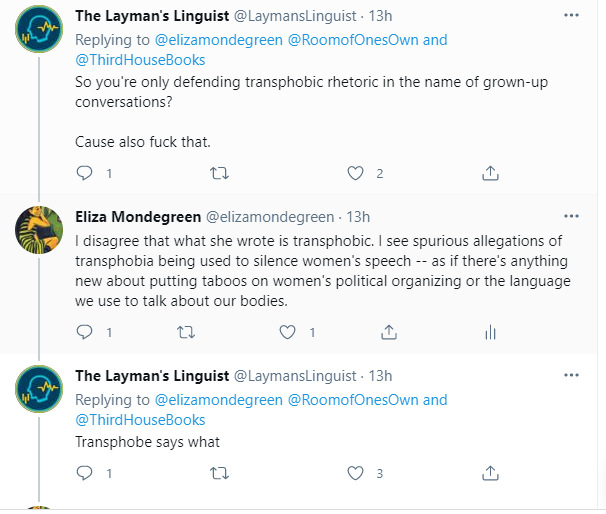

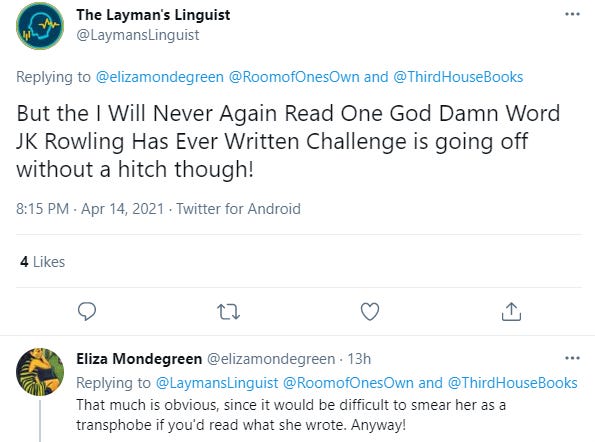

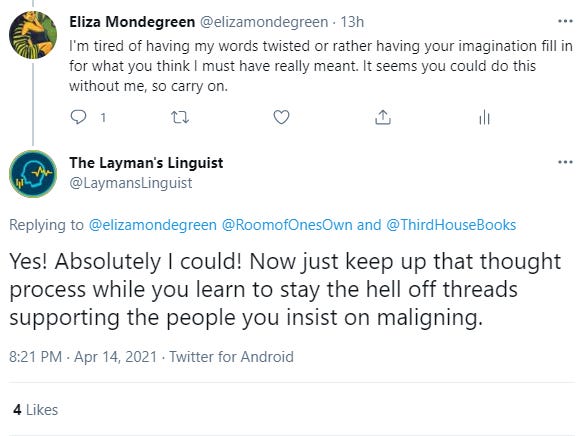

I spent most of our exchange pointing out I’d never said the things my interlocutor (if we can call him that) tried to put in my mouth, while he accused me of bad faith.

I encouraged a bookstore to engage with a woman’s words—and expressed concern that people eagerly condemn her without being able to explain why. They can only label and libel her, not engage with her, much less refute her.

It’s strange to be accused of saying things I didn’t say while defending someone else against accusations that she said things she never said. He’s reacting to something, but he’s not responding to me. And it’s strange to choose your words carefully—not to conceal but to clarify, to bring things in out of the dark—and to be relentlessly accused of concealing my true meanings and saying things I never said, the more efficiently to dispense with me as a bigot.

After awhile you feel invisible—your mere image is enough. What’s been projected on you is enough. It’s not a new feeling being told you don’t really mean what you say or being treated as whatever it’s been decided in advance that you are—be that hag or naïf or mark. Your insistence on breaking with the script, spoiling that image—venerated or fetishized or reviled—only disrupts the other person’s fantasy, and fantasies don’t like to be disrupted.

And then he rides away, sacred—or, in this case, decidedly profane—image intact. But he showed me, right? Never mind that he had to conjure me first.

But setting aside that thoroughly disemboweled strawman—I want to go back to that bookstore where I first found Simone de Beauvoir, Kate Millett, Adrienne Rich, Ellen Willis, Andrea Dworkin, Zadie Smith, and so many other writers. That bookstore changed hands—and philosophies—between my student days and today. I can’t imagine anything that would have made me feel unwelcome in a place full of books back then. It never occurred to me that the books a store sells should adhere to some party line. Or that when a writer veers from that line, no one who enforces it will be able to explain the crime. Part of the delight of the books I brought home were the arguments. Willis and Dworkin were dead and cold by the time I’d read a word they wrote and yet they crackled at one another and tugged me back and forth, agreeing with one, then the other, or disagreeing with both. They made me think, in other words. Every book I read contributed something, if only an argument to push against or the etymology of a much-handled word. Why should anyone agree? What would it mean to read only the right books, think only the right thoughts? Is that thinking or only rehearsing?

In any event, here’s to the memory of a feminist bookstore where women—living and dead!—once argued about everything.